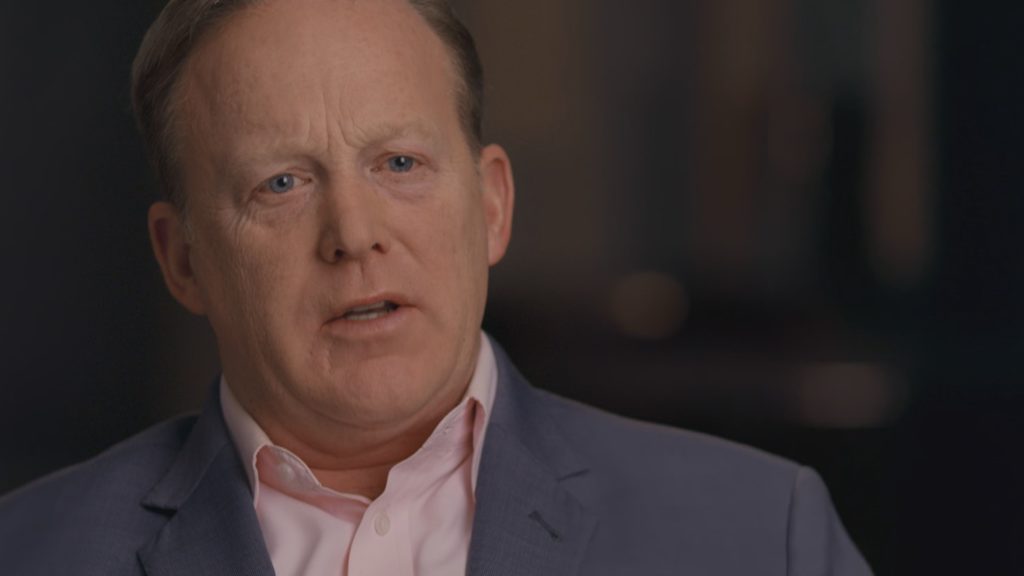

Sean Spicer served as White House Press Secretary from January 2017 to July 2017. Before joining the Trump administration, he worked as communications director for the Republican National Committee.

This is the transcript of an interview with FRONTLINE’s Michael Kirk conducted on Jan. 25, 2018. It has been edited for clarity and length.

Our film begins [on July 7] of 2016, when Donald Trump comes to Washington, the presumptive punitive nomnee, to visit the RNC [Republican National Committee] in the morning and go over to the Senate in the afternoon. Who is the Donald Trump that comes to town? …

Well, I think the RNC, as an institution, is there to latch onto whomever the voters choose. That being said, I think greater Washington, the political class and the establishment, if you will, weren’t prepared for this guy with no political background or, frankly, desire to embrace the political establishment, who traditionally had been part and parcel of a presidential campaign. I think it was a very interesting get-to-know-you period.

Was it a victory lap for him?

No, I don’t think that he—he was never about trying to win over the Washington class. It was never for him about trying to get or seek their approval. I think it was more matter of fact: “I’m here. I won. Let’s go.”

Yeah. And the Republicans, a lot of Republicans—he had beaten a couple of them that … some of the Republicans didn’t like, [Sen. Ted] Cruz (R-Texas) and maybe [Sen. Marco] Rubio (R-Fla.). But there were others, many others, that were just sort of like: “I’m going to hold my fire. I’m not so sure about this guy.” Give me just a sense, Sean, of the state of the Republican Party at that time. We kept reading civil war, Tea Party, Freedom Caucus, [Speaker of the House John] Boehner (R-Ohio) out, [House Majority Leader Eric] Cantor (R-Va.) out. Give me a sense, from your perspective, of what the state of the Republican Party [was] at that time.

Look, I think the party had done really well in the last midterm election. We had taken a large majority in the House and the Senate. We had a majority of the governorships. We had a majority of state legislative races, all the way down to municipalities. We had done very, very well as a party, and I think there was high hopes that we could carry it on and win back the White House after being out for quite some time.

There was a question about whether or not the Trump campaign had the political understanding and infrastructure to go into a general election against a very, very well-funded Clinton machine. The party, I think, has always had some degree of people who want to be outsiders, but largely within a group of people that are insiders. Trump was truly that outsider. He had no political pedigree, no background in Washington, no background in government or politics.

I think this was a phenomena [sic] that people in Washington, frankly on both sides, weren’t prepared for. It’s one thing to have a governor, a [Bill] Clinton, in ’92, who wasn’t necessarily part of Washington but had been involved in politics and party politics. This is somebody who not only wasn’t involved in party politics, hadn’t had an elected office, and frankly left a lot of people wondering what their role would be.

Did you meet him that time?

Yeah.

And?

Well, I had known the president. I had met him. He had been a donor. I had gotten to know him through the lead-up, after he became the presumptive nominee. And obviously, I led a lot of the debate work for the Republican National Committee through that period and got to know both him, some of his staff and a lot of the other candidates.

What did you think of him?

I had known him as a successful businessman or a reality television star, so I knew that he had—I knew him by reputation as sort of a guy who knew how to market well, was very gregarious and larger than life.

When he meets with the Senate, one of the stories we’re telling is the [Sen.] Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) stepping up and saying, “I’m the one that didn’t get captured,” or whatever. What did you make of that interaction? Or what do you make of it as you think about it now? What was Flake doing?

Well, I think for a lot of these guys, they weren’t sure what to make of a guy who didn’t necessarily play by the rules that had been governing party politics for a while, and I think he was sort of trying to figure out where those boundaries were going to be for someone like Flake. You know, you were trying to figure out who—is he trying to see where Trump is going to go, or is he trying to figure out where he’s going to go?

And he tests Trump in some way.

Well, sure. He tests himself, too. I think that’s the point, is that he’s trying to figure out, can I go here? How is he going to react when I go here?

And how does he react?

Look, I think Trump understood—Trump approached politics like business, which is, “Hey, I won; let’s move forward, but let’s be clear who the winner is,” in the same way that, when you buy a building or take over a company, you recognize that you’re now in charge.

So the campaign happens. Everybody’s sort of on the sidelines, or there’s some people who go along with him. But a lot of people in the Republican Party are sort of waiting it out. They really don’t believe he’s going to win. [Senate Majority Leader Mitch] McConnell (R-Ky.), [Speaker of the House Paul] Ryan (R-Wis.)—we’ve talked to 30 people this last couple of weeks here. They were all sort of stepping on the sideline. “Wait a minute. We’ll see. We’ll see.” Access Hollywood happens. Ryan is on the phone, says the thing, “I’m not going to endorse him.” For somebody like Ryan, when it’s election night, and he’s watching the results, can you imagine what he’s thinking about as he watches Trump start to win?

I think for a lot of people, there was no question that Trump had a path to 270, but I don’t think there were very many people, if any at all, who saw 306. You know, a lot of these paths talked about, how do you pick up a state that we traditionally hadn’t been able to get, but to see all of them fall in line? I mean, it’s literally like watching that lottery thing happen with the balls, and you’re kind of going, “OK, I got the first number and the second number,” and slowly in your head you’re going, “Oh, my goodness. I can’t believe that everything is lining up this way.”

For most Americans, for everyone in the media, for a lot of pundits, watching these states, one after another—Iowa, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin—all fall in was something that people just wouldn’t have been imaginable hours earlier.

And when you’re Ryan, and you’ve not endorsed him, you’ve not been with him, and it looks like you’re going to have to work with him, what are you thinking?

Whether it’s Paul Ryan, Mitch McConnell or a lot of other folks who have been around the block and been involved in elective politics, they understand that that’s how it works. You do what you have to do to advance an agenda, and I think frankly, if you’re Paul Ryan, you recognize that you now have an opportunity to achieve a lot of policy goals that have eluded you for, frankly, decades.

Getting back the White House when the alternative would have been a very, very far-left agenda set by Hillary Clinton, I think you actually are elated in the sense that you finally recognize that there’s a lot of things that you will finally be able to get done that weren’t even imaginable.

What do you figure he and McConnell were worried about, with a novice president coming out of the business world, a brash guy, a surprise victor?

Well, frankly, again, if you’re having to control the House of Representatives, that coalition needed to get to 218, or 51 or 60 if you’re McConnell, depending on—you want to make sure that you’ve got a partner that you know understands what you’re up against, has an appreciation for what you’re trying to achieve, and the balancing act that you have to do from time to time.

And this guy, as you size him up specifically?

It’s something that he is an outsider, and I don’t think he’s here to play Washington political games. He clearly continues to have an appreciation for it. He’s a dealmaker at heart, which is a good quality, and he understands what he wants to get done and what he wants to shake up. In that sense, I think that it works well. And so far, after a year, there’s a lot of results that prove that he’s getting it done.

Where are you on that night?

In Trump Tower with the president-elect.

And?

I’ve been asked before to explain the feeling, and I don’t think it’s one that I have ever felt before, nor do I ever think will happen again. When you lose and you think you’re going to lose, it’s one thing. When you win, and you think you’re going to win, it’s one thing. When you win, and you could win, it’s one thing. When you win big, and most people didn’t think he had a shot at winning, and you win against the Clinton machine, a machine that had bragged openly about a fireworks display and was making it very clear that they thought they were going to win, and New York Times had Hillary Clinton winning at 93 percent, and to slowly watch that evolution of results come in on the TV, and states that were supposed to get blown up by double-digit numbers, North Carolina and Virginia, and to slowly start to come in, Florida, and realize that it’s actually happening, and happening in a way and in a magnitude that nobody fully appreciated—

You feel surreal?

Yeah. Look, I’ve been in Republican Party politics for over two and a half decades. This is it. This is the Super Bowl. This is the Grammys. This is—you name your big night, your championship night. To be part of a winning presidential campaign, this is it for what you do, and you realize that you are part of history, and you helped somebody in some small way get there. It’s something that no one can ever take away.

For the people who are nervous about him, and maybe out of his own instinct, he writes a kind of unifying acceptance speech that night. How did he write it? Who wrote it? Were you there when it was being written?

No, I was not there. He went up to the residence. I think there was a draft being prepared, and then the president himself inserted much of that language. He, I think, truly appreciated the moment in time that it was and recognized the need to set a tone right out of the gate.

Could you tell what it felt like to him, by being around him that night?

Yeah, and I saw him not only then, but after he returned to Trump Tower that night. It’s one of those things that I think, human to human, you can see when someone is dealing with something, and the weight of that, of the election, the processing of recognizing what was about to happen, was clearly going through his mind at that time. You could see how profound the moment was.

And the braggadocio, the brash guy was gone?

I didn’t see it, no. I think I saw a man who truly understood what the transformation that was about to take place.

Yeah, I can imagine. It doesn’t take very long for Ryan to say, “This is what unified government looks like.” A lot of people we’ve talked to said they were thinking about who was Trump going to be by the time the inauguration happened. Would he be the pen? Would he have an actual agenda? Would he try to impose it on—because he’s different enough, and he wasn’t playing by the rules, and he wasn’t bound by any of it, that he would try to push something of his own through and along? You were around for a lot of the early stuff. What was it like for him getting his feet wet in those first few days, in terms of just dealing with McConnell and/or Ryan?

You mean in the White House?

Yeah, in the White House.

We determined early on that health care had to get addressed, more procedurally than anything else; that the arcane process that it works through, the reconciliation process yields certain tax savings that could be used for tax legislation because of how the Senate operates. That being said, there was a big get-to-know-you period in the sense that there was a belief, right or wrong, that because this repeal of Obamacare, this discussion about health care had been going on for so long, that there clearly had to be a plan, and the Congress clearly would know what to do. I think that … wasn’t necessarily the case.

You mean Trump actually believed—we’ve had other people who we’ve talked to from the administration say: “He thought, OK, they’ve had seven years, and they’re complaining. Forty different bills have been voted on at one time or another. For God’s sake, they’ve been in session for a while before the inauguration. There might be a bill right around the corner.”

Again, I think that’s right. I think there was an assumption, not just on the president-elect’s behalf but others’, that now that Congress had a Republican president coming in that they certainly would have a plan to rally around and a process to execute.

But they didn’t.

Well, they didn’t, but I also think that it’s a two-way street. I think there was a little bit of—there was a lot of assuming about who probably had what and who should have done what. I think a lot of earlier coordination would have gone a long way.

And why didn’t it happen?

Because—for a lot of reasons. First and foremost, all of it was new, and all of it was different. I think Republicans have been out of the White House for a long time. A lot of traditional Republicans, if you will, who had maybe served in one of the last two Bush administrations weren’t Trump supporters. They weren’t here to jump in and immediately be part of it. And I think frankly, a lot of the ones who wanted to had been very outspoken against the president’s campaign and candidacy.

It was very hard, I think—there was so much that was new, and there was such a goal of being transformational and disruptive to the process that a lot of the things that might have traditionally gone on didn’t get the attention that they probably deserved.

Did he articulate the disruptive party, or was that [Chief Strategist Steve] Bannon or [senior policy adviser Stephen] Miller or somebody else?

I think it was part of his image in the campaign and I think what he had articulated as his priorities and his style.

“Let’s go in and drain the swamp.”

Well, just to not make this a—it wasn’t just “Go in and blow things up.” It was sort of, “Let’s not assume that the political establishment class has all the answers”; that there might be a better way to do this, that this outside perspective, this business approach to looking at things might yield better results for the American people.

From outside, it looked like chaos, especially that first week or two. Was it?

There was some, sure. … Again, there are so many elements of new—new personalities, new agenda, a new … government approach that hadn’t existed for the Republicans in a long time. There was a lot of trying to figure out how to get things moving in the right direction and get people in the right positions to help shepherd through some of the early initiatives.

What did you learn about him in those first few days?

My big takeaway was that you can’t have a traditional operation and a traditional staff for a nontraditional candidate and a nontraditional president. He wasn’t going to wrap himself in every bit of tradition and protocol that past administrations had.

Like, for example?

I think that he was about getting it done and what had to happen. He met with steel executives early on and recognized that they weren’t going to be using American steel for the Keystone XL—Keystone XL pipeline and the Dakota pipeline. He thought that was crazy. If we’re going to go fight for American energy, why aren’t American workers at the heart of that proposal? And he said: “We need to rewrite these things right there, on the spot. We need to do what we have to do.”

He had met early during the transition with these leaders in the technology and information sector, and as they talked to him about regulations and issues that they had as companies, and as leaders, growing jobs, growing manufacturing, hiring more people, the president was very attuned to what does it take to get rid of that? What does it take to get rid of that barrier? He wasn’t willing to sit around and listen to discussions about the process. He wanted action, and he wanted it now.

And when Ryan, for example, comes in and has a PowerPoint about Obamacare and lots of other stuff, we’ve heard stories of Trump saying: “Hey, no, I don’t—you’re the detail guy. Get it done.”

It depends on the issue. There’s a lot of things that he was very detail-oriented in. I think part of it comes down to the issue, and what the exact meeting was. There was no cookie-cutter approach to it. It was what he knew about an issue, what the briefing was about. There was no one-way approach that he looked at things.

With repeal and replace on the Obamacare, what was his role? What did he and Ryan agree he should do?

Well, I think we clearly understood that this was something that Congress had to lead on. It had to get the issues on. This wasn’t going to be the two-year deal that Obama had done to try to get—and the fits and starts that they had had to do. We wanted to really get this thing moving so we could get onto tax reform and subsequently infrastructure, so we wanted Congress to focus on sort of an inside game. What was it going to take to get 217 votes in the House and 51 votes in the Senate? And that was it. It was an inside play to try to figure out what it took. But getting consensus among one of the chambers, never mind both, was something that no one counted on being as difficult [as it was].

A lot of people we’ve talked to said he was promised Easter from the House.

Right. And again, the problem is, is that for cycles, House Republicans had passed over and over again some version of repeal and replace, over and over again. I think you finally had a willing partner who said: “Great. You do it again, I’ll sign it.” I don’t think anyone fully appreciated the fact that doing it when it doesn’t count isn’t the same as doing it when it counts.

What does that mean?

Well, what it means is, is that when you get to vote as a Republican House majority, knowing that a Democratic president will never sign the repeal of his signature piece of legislation, you know it’s not going to pass. It’s almost like a free vote. When you suddenly recognize that the policies that you’re going to pass are going to go into law and have an effect on how people’s health care is delivered and how the cost curve is potentially bent, then it changes the discussion reel, because it’s not a free shot. You now actually know that what you do and say is going to have real and lasting consequences.

And did he know that? Did he understand that? Did he come to get it?

Well, I think the president knew it. That wasn’t the issue. I think the president was more frustrated that Congress wasn’t ready to go. There was an assumption by a lot that Congress, because they had done this so many times, so successfully, that it wouldn’t be that difficult to get it done now that you could actually know that it would get signed.

He has a certain affinity for [Rep.] Mark Meadows (R-N.C.) and the Freedom Caucus guys. [They] share the base, speak the same language.

It was also that there was a recognition. I mean, it was a math issue more than anything else. Meadows and [the Freedom Caucus], for a while, became the biggest bloc of votes that were gettable, that could get us to over the majority needed.

But they, of course, step up when it looks like Ryan is rolling it by them as fast as possible to get it on the desk by Easter or other things. They step in, and it seems like the president didn’t anticipate that they were going to become the stumbling block into getting this thing across the finish line in a hurry, anyway.

Yeah. I think that you’re trying to do the math, as far as what groups of members get you to the number that you need to get, and I think the Freedom Caucus clearly started to play a very, very outsize role in what would ultimately be success.

Meanwhile, he’s tapping the watch and saying, “Come on, Meadows, let’s go, and if you don’t, I’m going to primary you.”

And I think there was a level of frustration, because part of the issue was trying to figure out if we were trying to [let the perfect be] the enemy of the good and recognizing that we would have another bite at Conference if we get the Senate to get this thing moving, so get it over to the Senate, keep the momentum going, and then figure out how to smooth out the edges. I think that there were a lot of folks that initially had been helpful and then sort of were a stick in the mud.

The charge against Obama was he didn’t know how to slap backs. He didn’t know how to pull people into the Oval. He didn’t know how to get people on the airplane for a ride. Trump seemed to decide to do that, to go the other way when it came to lobbying the health care bill.

He did. The president recognized—but I think that’s the businessman in him, that he understands the backslap, the Oval Office lunch, the Air Force One ride; that that personal attention, those relationships can largely help hold one or two votes or make a lasting friend.

But Meadows, of course, tells us he was sitting there watching Trump try to chip guys off the caucus, and he’s pulling them back and tightening them down as tight as possible.

Right. There was a back-and-forth for a while. You’d pick up one, then you’d lose two; you’d pick up two, you’d lose one. It was constantly—it was very difficult to keep score for a while.

Is Trump in that game? Is he loving that game? That’s his wheelhouse?

Well, his wheelhouse is winning, and I think as long as the vote is going up, that’s his wheelhouse.

It wasn’t after a while.

There was a level of frustration when you would get someone onboard, then they’d slide back, or they necessarily couldn’t articulate what it was going to take to get them over the top. For a while there was clearly some frustration about where the vote totals stood.

Bannon gets sent over. Others get sent over. People get brought in. People from the White House are cajoling. At one moment it was called an ultimatum of people in the House, an outgrowth of something Trump said, or just people freelancing?

I think part of that was freelancing, people trying to do what they could on their behalf to get the vote, to get whatever votes or support they needed.

When Ryan comes over on that Friday afternoon and talks to the president, says, “I’m going to have to pull the bill,” are you there at the time?

I can’t remember if I was physically there. I’m not in the room at the time, no.

OK, so tell me what the vibe was. What happened around that?

Well, I think the president understood, and I think Paul—I mean, Paul knows the House Conference better than anybody, and he knew that not having a vote go down would be horrible; that there was a way, there was a path forward. That path forward might be pulling over for a little bit to let some of the issues simmer and people go back to the districts for a little while and then come back.

But he understood, and I think he wanted to make sure the president knew, that we weren’t giving up, but there was an opportunity to figure out what the best way to get some of those members onboard was going to be.

You of all people can understand how hard that probably was for Paul Ryan to walk into Donald Trump and say, “We don’t have it.”

Well, yes. But I also think they were in relatively constant contact, so it wasn’t a huge shocker. I remember the president at the time stopping and saying, “OK, let’s talk about what’s next.” The president wasn’t upset that day; he had been in regular contact with Paul and the rest of the leaders over in the House [so] that he knew where things were. It wasn’t a shock, because obviously, he continued to work [with] a lot of these guys rather frequently.

None of it was a shock in terms of what our vote count was and what their vote count [was]; [they] were very similar. So when Paul ultimately says that he’s going to pull the vote, it wasn’t a shock.

When Trump calls [The Washington Post’s Robert] Costa that afternoon—we’ve talked to Costa; we’ve read the news stories. Obviously, he calls in. He sounds bummed, depressed, like: “Jesus, this is horrible. We’re having to do this.” Accurate?

To some degree. But I also think that he knew it wasn’t over. You’re spending a lot of time and effort cajoling, selling, whatever you want to call it, and it was definitely a major roadblock and a morale bummer for us.

Yeah, the clock is ticking. Everybody is saying: “100 days, where is it? No major legislation. He’s failing.”

I think that that made it harder, is that no matter how close you got, until you got 218, you had nothing.

How did that feel around the Oval, and around the—?

It was tough. There’s no question, because you’ve got this internal sense of trying to work really hard to get to it, but then you’re hearing constantly, “No agenda. Couldn’t get it done,” and there’s no context to that, right? There’s no “Oh, it took Obama two years. It took 31 years for tax reform to ever get done prior.” I mean, they’re big things don’t come easy, and I don’t think anybody in the press corps was giving us any breaks, as far as saying, “However, it’s tough to get this done,” or, “They might have to go back.” Obamacare was fits and starts the whole time. They had to jam that thing through finally after a two-year effort, once Massachusetts’ [Republican Sen.] Scott Brown came in. They were afraid that’s how close it was. Frankly, the impetus that got it through was, “We’re going to lose this vote.” There was no context for us. To get everything done as quick as we did, to some degree, was a miracle in itself.

So it’s no wonder that in the famous Rose Garden celebration ceremony, there was an impetus by the president, by you guys, by the House, to celebrate.

Well, sure. I mean, you had been beaten down over and over again by the media in terms of being told that we hadn’t had a major victory, so it was obviously an attempt to make sure that that message wasn’t just heard here in Washington, but that the American people who were watching or reading saw people talking about an achievement being made and process being made.

But of course a lot of people say it’s spiking the ball on the 20-yard line before you’re in the end zone.

Yeah, I get it, and I think that under a normal course of action, that probably wouldn’t be recommended. You don’t want to do it halfway through the game. You still had to get through the Senate. Then ultimately you would have to get through either Conference or some kind of bill that got deemed. So yes, it probably isn’t the formula that you want to use going forward, but at that time, everybody needed something to cheer them up and to say: “Hey, guys, let’s go. Let’s get back on the team. Buck it up, and let’s move forward.”

… It’s at that time that out in the town halls in America, a lot of people have noticed they don’t like—and the Democrats have ginned up, a lot of stirring of unhappiness about the Obamacare repeal-and-replace ideas that were coming out of the House. Senators see it. The press is there. It’s a little bit like August 2009 in reverse. What is the president thinking about that?

We recognized that in order to do a major legislative effort the right way, there’s two aspects to it. One is the inside game. How are you going to get the votes in the House and the Senate, get that thing to the president’s desk and signed? The second is, how do you build the grassroots, grasstops, local leaders, local-opinion papers? How do you get that kind of broad American public support? We forego that second piece and just played it straight on, on the first, which was, let’s get this thing passed, because then we can get it done. Eventually people will see their health care costs go down, they won’t be losing their doctor, and we’ll be moving onto tax reform.

There was a bet that was made that if we can get this done by the time that—in a few months or a year from now, people will be seeing the benefits anyway, in terms of the cost that they’re paying for health care and the access that they’re getting for it. It’s a long-term play.

Was that a surprise to him to hear that that was happening out in the town halls in America?

No, because I think that when you saw—because a lot of the media coverage was driving a lot of that, and I don’t think that—it just reflected what members were hearing, was reflecting what we’re seeing on the national news anyway.

Was it his decision to play the one game and not both of them, or the other one?

Ultimately he’s the president; everything is his decision. But I think initially there was, you know, the team got together, the legislative team, and created a roadmap that said: “Here are the priorities that you have. Here’s the strategy that we think is best to achieve that.” And he bought [in] on it.

Leader McConnell goes behind closed doors with it, says: “We’re not going to do a lot of this. We’ll learn some lessons from what happens. He’s going to put 12 and 14 guys in a room, and we’re going to try to sort it out. I’m going to take a head count and get it going.” Trump says to them, “The House bill was mean,” at least the way it’s reported, and a lot of the members of Congress say—Republican members of Congress say, “Wait a minute; I took some hard votes for this guy.”

As I said, Trump is the ultimate salesman, so he recognized, “The House already voted; now I’ve got to get to the Senate.” Frankly, when it came to health care, he talked about a bill with heart. He understood, as someone who employs a lot of people, what health care means to a family or an employee. So I get it. It probably didn’t help relationships with some of the House members, but he wanted to do what he had to do and say to get it through the Senate.

In a way, it’s his thing. He doesn’t care about—

To the extent that the House had voted, it had gone to the Senate, and now the play is there, so focus on what you need to do to get the sale there.

In making the sale, [Sen.] John McCain (R-Ariz.) comes out and does a thumbs down. Where is the president? Where are you when you see that happen?

I think we were in the president’s—the dining room off the Oval Office. It had been tough, because we were all cheering for John McCain in terms of what he had just been diagnosed [with], and knowing what he had been through, you wanted him personally to do well. But it was a real big disappointment, because it had been this sort of coy game of where … that he had given early indications that he would be with us and with the rest of the Republican Conference. So it was a big disappointment to see it.

The president calls him that night before he’s on the floor, calls him. He goes out into the cloak room, talks to the president on the phone. Do you know what the president said to him?

I don’t.

He comes back, and he votes no. Implications to the White House?

Well, no. At that time, it was pretty clear who was responsible, right, I mean in the sense that we were one vote short, and it was pretty obvious where that vote was.

President is not happy about it. Goes back and forth with a tremendous number of tweets, aims at Leader McConnell. Probably doesn’t surprise you, knowing the guy. But what are we supposed to make of it? What are we—?

Look, all I can say is that I think there was profound disappointment that we were that close and that we had spent a lot of effort really believing that we could finally do something that Republicans had talked about for a long, long time, for what I believe, most of us believe, is the greater good, when it comes to health care. So it was a huge disappointment all around.

Yeah. I didn’t ask you about something that I just want to get your thoughts about. It’s the shooting of the Republican baseball team in, I guess, Alexandria, [Va.], wherever it was. Can you talk a little bit about that? What happened? What was the president’s response? What was the White House’s response?

That morning, I think it’s just around 8:00 in the morning, we start getting early reports that there’s been a shooting. And obviously, for the next little while, details came in. I called the president to make sure that he had known. I think there was a lot of people who called the president that morning to make sure. Like any tragedy, the closer it is, the harder it hits. And it was a very, very difficult time because there’s also a lot of chaos. Reports were coming in about what had happened, who had been hit, what their status was, what the status is with the shooter, where it was.

For a lot of folks, that’s a field that a lot of people have gone by. That’s a game that people have played—there’s a lot of aides that played congressional softball or congressional baseball. There’s a lot of people who go to the Congressional Baseball Game. There’s a lot of members and staff that attend those practices that we know, and it was a very—it hit close.

I knew that the president—again, it was one of those moments that weighed heavily on him personally, because you’re seeing someone get targeted purely because of their beliefs. I think that for so long, folks from the left have sort of tried to intimate the right’s involvement or ideology as part of other things, and to see now literally a shooter go out and say, “Are those Republicans? I’m going to go after them,” was just chilling.

A lot of people say it’s the definition of divided states of America. Here we are. We’re now that divided. The pendulum is that far apart, and it’s been exacerbated by the Trump administration.

Well, look. I think it is a sad state of affairs when somebody literally says, “I’m going to take a gun and target people purely because they are Republican or conservative.” They are lawmakers. Attack them and try to kill them, that’s—you know, that wasn’t even like—there was no—I mean, that was his stated goal … That’s what’s sad, is that there was a person who literally went back and got a weapon to hurt, kill people purely because they are conservative.

After the health care bill goes down, [Chief of Staff] Reince Priebus is let go. I’m watching on television. Air Force One lands; he walks alone in the rain down the thing. Then he gets in a car, peels off, goes another way. You’re close to Reince. You’re there maybe because of Reince in lots of ways. What were your thoughts?

Well, it’s difficult when somebody that you know is going through a tough situation, and I think for myself, for Reince, for a lot of other people who really worked very hard, and frankly, in a town that a lot of people questioned whether or not it was the right thing to do … it was tough, because you’re watching somebody who you know has fought really hard, has spent time away from their family, has given a lot and sacrificed a lot personally to help enact an agenda or be part of something.

I think this is true of anyone, whatever party that you serve on. There is a tremendous personal sacrifice in terms of your time and your ability to be with your family or your friends, and to watch somebody not be given the proper due is difficult.

Why did that happen? Is that Trump at his worst?

Well, I just—I think that’s when it is who he is. When he’s ready to change things, when he’s ready to make a decision, he makes it. But I don’t think it’s any surprise. Again, you know, he is who he is, and he—and he executes pretty much to what people believe he would do.

These things he does, though, the Priebus, you, Bannon later—I’m not equating all of you, but there are demonstration projects in ways. He’s sending messages. His Flake moments, [Sen. Bob] Corker (R-Tenn.) moments. It’s almost like there is a kind of, “Hey everybody, you stick with me, or your end can be inglorious.”

Right. But look, he is a nontraditional, nonpolitical candidate, and I think that it’s tough for some people to sort of go, “OK, he’s a nontraditional nonpolitician,” but then assume that he should do things according to what a typical politician or person does. That’s just—it’s not who he is. He got elected saying: “I’m going to be different. I’m not going to do what’s normally done. I’m going to shake things up.” So to assume that he would do anything different just doesn’t make sense on its face.

So for you, when you look back on it?

What about it?

Well, was he effective?

I think policywise, at the end of his first year, when you look at where the economy is, there’s no question that we made tremendous strides in both job creation, consumer confidence, the stock market, and people’s 401(k)s are better off. I think there’s a lot of innovations. He’s made tremendous strides in veterans, defeating ISIS, getting immigration down. He’s done what he said he was going to do.

I think if you bought into the Trump agenda, he’s getting it done. If you oppose the Trump agenda, I think you at least have to admit that things are getting done, and things are definitely not the same in Washington.

Let’s just spend one more moment on Jeff Flake, and then we’ll see if we forgot something. …

The thing about Flake that’s interesting is that I don’t think there are a lot of these politicians that don’t recognize the new reality, and I think that Jeff Flake thought that he would be rewarded by attacking Trump. In fact, he had announced that he wouldn’t seek re-election. That’s not normal. That’s not how Washington normally worked, and I think it caught a lot of traditional politicians off guard.

What do you mean it’s not how Washington worked?

That normally, if you thought something that I think that he thought, by standing up to Trump that he would get credit from the base. I think the base doesn’t necessarily agree with everything that Trump says or does, but they’ve been so tired and so forgotten that they’re willing to tolerate things that they might not always agree with if they believe that they’re going to get the change and outcomes that they think that he will deliver.

… When he goes to Arizona and says, “My staff won’t let me say the names,” but it’s clear he’s talking about Flake, and he’s with Sheriff Joe [Arpaio]. Clear he’s talking about Flake. Clear he’s talking about McCain. He invites Flake’s opponent. Pretty direct.

Yeah, look, he’s a streetfighter from New York. This is not a Washington politician. And he has made it very clear that he doesn’t sit back and just take the punches that a normal politician would. He fights back.

It’s evident in the Corker thing back-and-forth. What did you make of that?

Clearly the president and I have very different styles about how I would approach things, but he is who he is. Part of it is that, again, I’m not sure that that’s a tactic that anybody else could use successfully, but that’s how he fights. He thinks that you can go in, you fight back, and then, as was seen, within a month, Corker’s on Air Force One flying down to Tennessee with him. That’s his MO. He pushes back, he fights back, and then they try to—most cases, it all patches up.

Except for Flake, who goes on the floor of the—

And look where Jeff Flake is. He can’t run for re-election. He’s kind of been marginalized. Flake took the shot and I think realized he missed. But even Corker came back into the fold. There’s very few people who have—I mean, if you look at what the trajectory is of the guys who have attacked him, they’ve largely been marginalized.

And this is not lost on Republicans.

Correct. And frankly, again, I think he set a very strong—the roadmap’s there. If you attack him, he’s going to hit back, and he will probably win.

And when Flake says, “But Charlottesville is something else. It’s a stain on the party forever. This is something that the president of the United States, who is a Republican, is talking the way he talked,” especially that press conference at Trump Tower. Were you there?

No.

No. So there it is, the president. Then Flake says to us: “Stain, stain, stain on the Republican Party forever. I had to speak up, and then I had to leave. I knew I was going to lose anyway. And then I had to leave.” Stain on the Republican Party?

I don’t agree with that. Obviously there’s a lot of words that could have been used better. It’s a very painful, hurtful point for a lot of people in our country to watch that happen, and a deep recognition that we still have a long way to go. But I also think that a lot of people threw around a lot of motives that might not have been, that misstating words or not being thorough was more to blame than anything, maybe, in someone’s heart.

You mean in his heart he’s not a racist?

Right. I mean, it’s not that he’s not—I mean, I just—I think that that’s, again, I think once the war of words started up, it didn’t do anybody any good.

Were you in meetings and things where you said to him, “No, no, no, don’t do this”?

No. At that point, I was still onboard, but I wasn’t doing the day-to-day stuff.

A little marginalized at the time?

Yeah, intentionally.

Let me ask you a question, personal question. It was the Melissa McCarthy thing [on Saturday Night Live], but it’s also what rolls down with the best of late-night shows. Open the Times, it’s all the jokes about President Trump. Stephen Colbert makes a career out of it, gets millions of dollars out of it. Give me a sense, from your perspective as the press secretary of the United States of America, what it was like, what that was like. Did it infect the process in any way?

Well, there’s two things. On a personal level, it’s very weird going from zero to 100, from going from—I’ve been the party spokesman for six years. I could pretty freely walk down a street and—and to suddenly get thrust into that was just an experience that is almost indescribable, because it went so quickly and so intensely. With respect to the late-night aspect of it, you’ve got to be able to take a joke if you’re going to be in this business, and I think I’m pretty good at that. Some of it was funny. You literally would watch some of these YouTube clips—because I rarely would be up that late to watch them, or even if I was, that wasn’t what I was watching—and there were plenty of times when you would just laugh at yourself and say: “You know what? That was funny.”

There’s a difference between funny and mean. That’s the line, is that being able to laugh at yourself or understand that a meme or a narrative is out there about you, sometimes self-inflicted, but it’s funny. That’s one thing. When it crosses the line and is mean-spirited, I think that’s a lot harder, personally, to do. Again, it makes the atmosphere more difficult, because you’re operating in a sort of meme world, where you try to figure out the littlest thing that you do becomes Internet sensation.

And for the president himself, did he watch those things? Did he care?

I don’t know. I think he cared, frankly, more about those around him, his staff and others, than himself. He’s been in the limelight for so long, I think that he’s used to a little bit of the criticism, the critique and the caricatures. But I think he actually probably thought it more difficult to see his staff and his inner circle thrown into that.

They like to think that they’ve had a political effect, that they’re pushing back against something in a way that even the press doesn’t push back. They push it as far as they can. Are they having a political effect by your lights?

To some degree, I think so. I mean, I don’t think that there’s ever been this full-on effort by all of the shows to make politics, you know, conservative politics and/or Donald Trump the mainstay of what they do. It used to be that you would not talk about sex, politics or religion, and now you have to talk about politics. You have to know what’s going on. It’s water-cooler conversation. To not know what the latest tweet was, what the latest viral video is, is almost like being out of the loop. They have really made it a mainstay now of those shows to figure out how to push the envelope, be more outrageous, particularly when it comes to attacking the right.

So along with talk radio, along with the Breitbarts of the world—so we’re talking about changing landscape that meets Trump and that Trump rides in some ways and is infected by—along comes all of this comedy stuff that also is a voice that’s just in the air all the time. That’s another part of the change that you were talking about.

Right. But the big difference is, is that because of the Internet in particular, … those little vignettes and skits suddenly would go viral. People were sharing them on Facebook, pushing them around via email, whatever, so you’d actually have a lot more people seeing a lot more stuff. Plus, I think there was this sense to figure out, which late-night person, which YouTube star could outdo the person and be sort of more offensive, more crazy about what their portrayal of the administration was.

It must be very weird to work in the White House, and in the morning, and then hear the—whatever the policy was, whatever the fight was, whatever the Corker things were, whatever the Flake things were, whatever the decisions were, the votes were, the McCain moment, it’s all comedy and vitriol and arguments out there in the landscape that have nothing to do with—I mean, when the person in your job was Bill Moyers or somebody else walking out to the podium to intone on behalf of the president, it was a much different world than the world you lived in.

There was actually discussions about issues and policy. It became an attempt most days with trying to figure out what the next meme was going to be. What reporter could yell the loudest? Which one could be the most obnoxious? What YouTube clip could go more viral? That is a very different atmosphere.

It wasn’t too many years ago that in meeting with a lot of the media organizations, politics was on the outs, that that’s not what people wanted to watch. It was tuning out viewers. I don’t think—from the time people wake up until the time they go out to bed now, politics is front row, and in large part [because] of our news shows, our late-night shows, and most of the stuff in between.

And that’s Trump-caused?

I think a lot of it’s Trump, sure. I think it’s this intersection of culture, politics, policy, all colliding at once, and largely driven by Donald Trump.

I know people ask you this, and I’m going to have to ask you, because I have to: Did you lie on his behalf?

No.

Never?

No. There were plenty of times when—look, your job, you may not go full on, but I don’t think that that’s your—I think the job of the press secretary is to articulate what the principal wants articulated, not what you want. You’re not there to call balls and strikes and interpret. So when asked, “What does that person think?,” your job is to say, “They think the following,” not, you know, “However, I believe that this is a better…”—I mean, that’s not the job.

So the stuff about the size of the crowd and all that stuff was you doing your best to reflect—?

It was. And look, I’m not here to relitigate the past, but if you actually look at what I said, first, I would say that we—“we” meaning me as the person that went out and led the team—could have unequivocally done a better job. That was a—and I’m not making excuses, but it was a Saturday night of a three-day weekend of the first day, and we’re trying to figure out what’s going on, and we’re trying to push back against a narrative that kind of just got developed out of nowhere that we felt was inappropriate.

That being said, I think that when you actually look at what we couched and talked about how—you know, viewed, and we tried to build it up, because there were certain platforms that, frankly, hadn’t been around eight years prior. We had seen some of the numbers that had come in from online and others, and we were trying to push back on a narrative that we thought was sad, in the sense that here you have a president get inaugurated, who is historic by all means, who had a pretty, pretty profound inaugural address, and you have these commentators trying to figure out how many people were there or not. I think it’s petty on their behalf, and I think that the president, rightly so, was a little taken back by that approach.

Meanwhile, you’re working for a guy who doesn’t want to put up with any stuff from the press on that or any[thing] like that, so you’re in the middle of that.

Yeah, absolutely. And I think it was tough trying to figure out, how do you balance making sure that we’re pushing back, but doing so in a way that, you know, still gets results.

Pretty intense, those moments. Welcome to the—

I mean, it was a pressure cooker every day, and a level of intensity. And I don’t think that that’s just my job. I think if you talked to previous press secretaries—but there’s no question we turned it up a notch. (Laughs.)

… So if the party was in some trouble at that moment, is [the tax bill] just wallpaper over more serious fundamental infrastructure problems in the party, where the moderates like Flake and—the establishment figures like Corker and Flake and others are pulling out? Also a lot of guys from the House, a lot of people from the House—that this is just a wallpaper that says, “Yeah, everything’s OK in the party,” or, “This is Donald Trump’s party, and it’s going to be different, and it’s going to move another way,” heading to very perilous midterm problems in the fall?

I think getting tax reform done was not only critical, but will have huge positive effects. You’re seeing the market go nuts, employees reaping the benefits, companies talk about hiring and investing. And as the economy continues to really move forward, and I think above 3 percent sustained growth for now, heading at least into the third and fourth quarters in a row, is going to be a huge thing. That’s going to help the party, and it’s going to help—it’s going to help the country.

But it’s a unifying thing. Taxes, reform, the economy, jobs are all things that I think all Republicans, depending on where you—you know, regardless of where you are in that spectrum, is a unifying message and tactic. And I think that that’s—it was needed at the time, and it’s going to be very helpful, because it carries through for so long.

It’s interesting. You look at that photo at the back of the White House, and there’s everybody lined up. There’s [Sen.] Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) saying, “It’s this guy.” A lot of people in the Republican world who were pretty worried about him at the very beginning, all the way through health care, like, “Oh, who is this guy?,” Charlottesville, “Whoa, who is this guy?,” [Judge] Roy Moore, “Oh, who is this guy?,” suddenly they’re all in line, and they’re saying hosannas to Donald Trump. Is that real?

Oh, I think so. I think on issues—the rollback of the regulatory state, tax reform, the economy, bringing jobs back, manufacturing, getting our trade balance back into effect.

[Supreme Court Justice Neil] Gorsuch.

Gorsuch, the number of conservative judges that we’ve put on—when you talk about the policies and the results that the president’s gotten, and you focus on that alone, you’ve heard the Heritage Foundation talk about he has been more in tune with their agenda than Reagan. When you look at the evangelicals talking about him pursuing an agenda that’s pro-life and respecting the social conservative agenda that Republicans have fought for for decades, he gets huge marks.

And I think that’s the thing. When you actually scrape away all the rest and focus on the results, the policies, the achievements, there’s no question that he is pursuing an agenda of change, but also a very Republican agenda.

Is it Trump’s party?

Sure. I think that whoever is the president, that’s by definition the leader of the party, because you can’t—they set the tone; they set the agenda. There’s obviously a lot of leaders in a party, but there’s no question that you can’t, whenever you have the White House, that president is the leader of that party, regardless.